What Does a Muscle Do?

At my Restorative Exercise certification training in spring of 2014, Katy Bowman, the founder of R.E. posed a question to our group – “What do muscles do?” Her answer – “they respond.” To be honest I didn’t give her comment much thought at the time, but since that day her words have come back to me time and time again and the truth of them has been born out of my experiences working with clients and in my own body.

What do we typically think of when we want to affect a muscle? Generally either stretching it or strengthening it. If I want to stretch a muscle, what do I really want to happen? I want that muscle to change it’s length. Specifically, I want that muscle to be longer that it currently is.

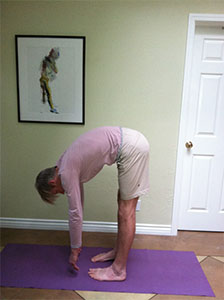

Let’s say I find out I have tight hamstrings and that having tight hamstrings is not a good thing so I decide I’m going to stretch them. I stand and bend forward and try to reach the floor, pulling strongly on the muscles in the backs of my legs. It certainly feels like I am stretching my hamstrings, but usually I am stretching the muscles in my back even more. In fact, because of the difference in the way these 2 groups of muscles are meant to function, the way that the hamstring muscles and the muscles in my lower back “respond” in this scenario can be very different than I intend.

The hamstrings consist of three muscles located on the back of the thigh which are called the semimembranosus, the semitendinosus, and the biceps femoris. The primary job of the hamstrings collectively is to extend the hip joint (pull the femur back relative to the pelvis) and flex (bend) the knee. When the knees are kept straight and the hips are flexed as in a standing forward bend, the hamstrings do the job of hip extension by acting as the main muscles that support the weight of my upper body as it moves forward and down. In other words, as I flex my hips to bend forward the hamstrings apply a counter force in the opposite direction, that of hip extension, to help carry the weight of my pelvis, trunk and head.

In this example, the muscles in my lower back have a job to do as well, particular the erector spinae whose job it is to help stabilize my spine and prevent it from distorting to the point that it puts undue stress on the spinal joints. These muscles work in combination with my hamstrings and my gluteal (buttock) muscles to enable me to bend forward without damaging the very important and essential tissue contained within my spinal column, namely the spinal cord.

Thus the job of my hamstrings in a forward bend, as well as those of the lower back, is to “respond” to that movement by acting as a kind of breaking mechanism, carrying the load of my trunk. Of the two muscle groups, the hamstrings are the bigger and stronger and therefore should be encouraged to do more of the work in a forward bend. For the hamstrings to respond this way I need to emphasize bending more from my hips and minimize the bend from my lower back. When the hamstrings are tight they don’t allow for much movement from the hips before they can no longer respond to my motion of bending forward.

If I keep bending forward, even when the hamstrings cannot respond anymore, then my lower back has to carry the load instead. My head and trunk are pretty darn heavy and therefore this puts a lot of stress on my back. If I keep doing my forward bend this way not only will I eventually hurt my back, but I will also not make much progress in increasing the length of my hamstrings. That’s because when I bend well beyond the range of my hamstring length the hamstrings cannot respond anymore and therefore will not increase their length. Meanwhile the muscles in my low back will respond, and quite appropriately, to the consistent excessive loading I’m putting on them by getting weaker less able to effectively do the job of maintaining a functional position of my lower spine that keeps the joints healthy, mobile and pain free.

This is just one of many possible examples of the way in which muscles respond to the input we give them in both helpful and not so helpful ways. Therefore when I recognize that I have a muscle that hurts or that is too tight or too week, before I go about stretching or strengthening I should consider what I may already be doing that is causing the muscle to respond as it is.

In the example of my hamstrings, I need to consider how much time I spend sitting or wearing shoes with heels or standing with my pelvis tucked. Any of these “activities” will result in shorter hamstrings because when I engage in these very common activities I am effectively telling my hamstrings to shorten. My tight hamstrings are just responding appropriately to the message I’m sending!