Applying DNS and Core Stabilization in Yoga

Several years ago when I was deep into Katy Bowman’s bio-mechanical approach to postures and movement I began to better understand some of the postural habits and faulty mechanics that were impacting my health and the health of my clients. It became clear to me that it was these habits and their frequent repetition while standing, sitting, squatting, bending forward and walking that lead directly to the manifestation of the chronic injuries and pain patterns that are epidemic in our modern lives. I also understood that if we were to overcome our injuries we needed to address them at their root cause by changing the way we move.

As this understanding came into focus, I started to take a closer look at the yoga postures I was doing and teaching and I had a realization. Those of us who do yoga tend to bring the very same postural patterns and poor mechanical habits we use in our daily lives into our practice of yoga postures. Therefore going to a yoga class often amounts to simply finding new and interesting ways to reinforce our patterns and promote our injuries.

This opinion is partly based on the fact that yogasana or the practice of yoga postures is extremely difficult. The posture themselves are for the most part so complicated and demanding that anything approaching mastery may arguably remain elusive for most. Yet it is also this degree of challenge posed by yogaasana which is the very thing that makes it potentially so powerful. If I manage to master even one posture I will have overcome much of my habituation, physically and mentally.

With the manifestation of this view I began changing my approach to practice and to teaching. I started introducing simpler postures that were more accessible and less physically demanding. I also began to emphasize the development of movement skills that could be applied not just to yoga but to the movements we do all day long. After all, what good is my trikonasana if I can’t bend forward properly to pick something up or squat down to use the toilet.

I then reintroduced some of the classical postures, not so much as postures to be mastered but rather as opportunities to apply the skills learned in the simpler postures to decidedly more challenging ones. The classical postures put the skills we learn in the simpler postures to a strong test, and they provide an opportunity to apply multiple skills at the same time. I liked this approach and still do, but until recently I felt there was something missing.

With the addition of my DNS training I feel I’ve found that missing piece. It’s the skill that integrates all of the other skills and organizes them into a cohesive whole. It’s the skill that transforms a set of applied skills, movements and stretches into a true asana – a posture that expresses both stability and ease. That skill is the skill of stabilizing the pelvis and trunk in a way that not only allows but in fact facilitates free movement. This skill is true “core stabilization.”

The DNS approach to core stabilization is not something I ever learned in a yoga class, but it applies to yoga wonderfully! I feel strongly that it’s a skill that has the power to transform any yoga practice. And for those who don’t practice yoga, proper core stabilization will improve whatever movement practice or sport they choose to do, not to mention greatly improve the movements they do outside of any structured class or activity.

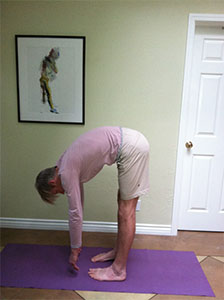

I’ve begun to post a series of short videos in which I offer an approach to setting up some of the more common classical yoga postures. The videos also include some voiceover cues for guidance. My approach to each of these postures emphasizes core stabilization as the foundation for each. I don’t necessarily use the term “core stabilization” in the video, but hopefully as you watch these you’ll begin to understand what I mean when I say “stabilize” or “stabilize the pelvis” or “stabilize the lower trunk,” and you’ll begin to apply this in your own postures.

Before watching these videos I recommend watching the more basic DNS videos that are already posted. It’s important that you understand how to breath diaphragmatically and to establish intra-abdominal pressure before you can do the kind of core stabilization I am referring to in the post and in the asana videos. Just click on the links above to view those videos before moving on to the others.

If you’re new to yoga, these videos are not meant for you. They are intended for students will some experience. If you’re an experienced yoga practitioner or teacher, I ask that you keep an open mind. The feedback I’ve been getting these days from the experienced yogis that find their way into my classes is that I’m doing something very different from what they’ve been taught before. Hopefully this makes for a great reason to take an interest and see what might be of value and not a reason to reject it simply because it doesn’t sync with past experiences or understanding.

Whatever your view, my practice and my teaching have always been and always will be a work in progress. Therefore I welcome your comments and look forward to hearing from you and getting your feedback. No doubt your input will help me refine and improve my practice and my teaching moving forward.

Namaste’