Genetics and Health: Why Diet and Movement Matter

The other day I received an email from a good friend and client sharing a link to an article in the NY Times. The article discusses a recent study done with participants from an earlier study, completed in 2003, on the effects of exercise. This earlier study, done at Duke University and called “STRRIDE” (for Studies Targeting Risk Reduction Interventions through Defined Exercise), took several hundred individuals identified as sedentary and overweight and randomly assigned them to either a control group or one of two exercise groups. The two exercise groups included one that did “moderate” exercise, such as walking, and one that did “vigorous” exercise such as jogging. The exercise groups did their assigned exercise for 8 months. The control group did not exercise at all.

As you might expect, both exercise groups showed marked improvement in several health markers including aerobic fitness, blood pressure, insulin sensitivity and waist circumference, while the control group generally showed no improvement. For this recent study individuals from each of the groups were invited back to the lab for testing to see how they were faring. Those that agreed to come back were tested for aerobic capacity and metabolic health and were asked about their health conditions and medications.

Not surprisingly, those from the control group in the original study were even less fit now than they were in 2003 while those from either exercise group were still better off than the control group. Less obvious but still not surprising was the fact that those who had done “vigorous” exercise in the earlier study showed greater aerobic capacity than those in either the “moderate” exercise group or the control, losing on average only 5% vs. a 10% loss in the other two groups.

But what was very surprising to these scientists was that the “moderate” exercise group, who had only walked 3 times a week for 8 months during the earlier study, showed substantial improvement in blood pressure and insulin sensitivity compared with both the “vigorous” exercise group and the control group. NOW THIS IS THE MOST INTERESTING PART – these walkers also showed these lasting improvements to their health EVEN IF THEY HAD STOPPED WALKING AFTER THE 8 MONTHS! William Kraus, the professor of medicine and cardiology at Duke who oversaw the study suggested that the effect of exercise on our genes and our cells might explain the study’s findings.

I regularly have conversations with clients who ask me “is this problem something I can do something about or is just my age?” I always encourage clients to avoid chalking up problems to age, even if age might be a factor, because once we decide that some pain or loss of function is due to age then it places that issue into the category of “PROBLEMS I CAN’T DO ANYTHING ABOUT.” Once a health issue is put in this category it robs us of the capacity and motivation to do anything to improve it, and there’s just about always something we can do to make things better.

I see deferring to genetics in a similar way. If we make the assumption that a health issue we have or might develop is due to our genes, even if our mother or father did have the same condition, then it hampers our ability to deal with it in the same way that saying a problem is “just because I’m getting old” does. As long as the problem is under the “CAN’T DO ANYTHING ABOUT IT” umbrella then we’re unlikely to respond effectively.

Studies demonstrate, and pretty consistently I might add, that the health issues that most of us are dealing with or that we are most concerned about are caused by genetics only about 10 to 30 percent of the time. The other 70 to 90 percent of the time these health issues are caused by diet and lifestyle. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in particular have been shown to manifest much more from lifestyle causes than from any genetic predisposition. Not only that, but it’s also been demonstrated that changes in lifestyle can influence our genetics so as to increase our genetic resistance to a chronic diseases such as cancer.

A 2016 pilot study done at The University of California San Francisco revealed that men with low risk prostate cancer who had decided to forgo treatment unless the disease progressed could improve the genetic markers for cancer by changing their diet. These men followed a diet outlined by Dr. Dean Ornish, and the men who followed this diet for 3 months saw some 500 genes change as a result. This included some tumor-suppressing genes that became more active with the change in diet, as well as some genes associated with increasing cancer risk that had switched off. The study did not set out to determine whether or not the changes in diet led to better long term health outcomes, but the changes in these men’s genetics were significant and promising.

Clearly our dietary choices are a powerful force for influencing our genes and any contribution those genes might make toward our manifesting a health problem, but what about our lifestyle choices? In her groundbreaking book, Move Your DNA, Katy Bowman argues for lifestyle, in the form of our daily movements, as a huge contributor to the health of our genes and their expression. She illuminates the important role of movement in gene expression by highlighting the difference between the genome and the mechanome.

The genome is the gene that we tend to think about when we think of our genes. This is the gene that resides with all our other genes in the nucleus of each and every one of our cells. This gene expresses itself by activating certain physical and/or functional characteristics that make us who we are as an individual. The mechanome is made up of this gene plus all of the exterior forces, many of them mechanical, that play a role in determining if and how a particular genome will be expressed.

To think of a gene as the primary actor in determining our health outcomes is like imagining some kind of stealth bomb in our body that will some day, likely when we least expect it, set off its charge and send us cascading toward some miserable end. Alternatively, the mechanome model presents a gene that is flexible and responsive to input, particularly movement input, and one that can, given the right input, just as easily contribute to a positive health outcome as a negative one. Therefore the amount and way we move, both a huge part of our lifestyle choices, can be a significant influence on our genes and how they influence our health and longevity.

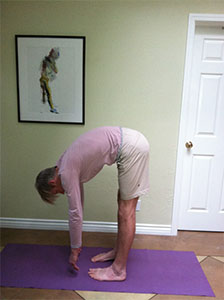

Movement choices are like the dietary choices we make in that they provides us with yet another powerful tool by which to influence our health on the genetic level. In a recent post on yoga for health I discussed the role of mechanotransduction in movement and I describe how movement can be used to influence tissue health on the cellular level. Although I highlight yoga specifically in that article, yoga is just one example of an approach to movement that provides effective ways of using mechanotransduction to affect tissue health. Yoga is intelligent movement, but there are other ways of moving intelligently that can have similar benefits. Walking for instance, appears to have played a significant positive role in the gene expression of the “moderate” exercisers in the “STRRIDE” study discussed above.

It should be encouraging to all of us, and especially those of us who worry that our genetic makeup may be undermining our health and function, that the studies mentioned above show we can improve our chances of better health outcomes with diet and exercise / movement, even if we have genetic predispositions. These studies reveal that we needn’t be at the mercy of our genes and that we have it within our power to change our genes in ways that are positive and lasting.